Predictions: From Minitab to Mindset Shift

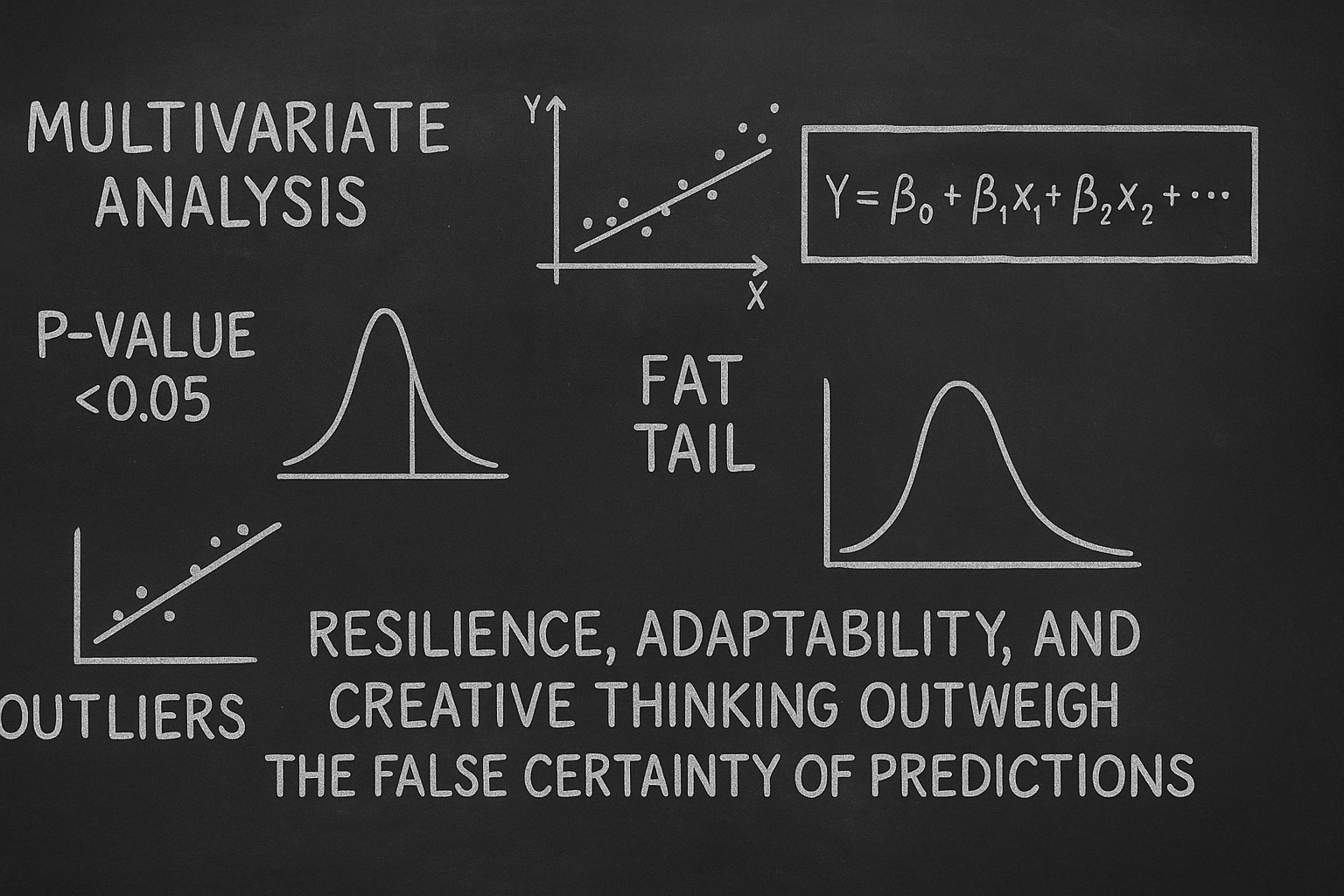

A journey from Six Sigma regression in Minitab to realizing that in complex, fat-tailed systems, resilience, adaptability, and creative thinking outweigh the false certainty of predictions.

Years ago, during my Six Sigma Green Belt project, I found myself deep in the world of Minitab, running multivariate regression analyses. The thrill was in the numbers. Inputs, outputs, R-squared values — each run felt like decoding a secret about the future. I believed, with near-religious conviction, that if you had enough data and the right statistical model, you could see around corners.

I was wrong — or at least, only half right. As my career evolved, I began to see cracks in that belief. Regression lines were elegant on paper but brittle in reality. The further my decisions were from the neat, controlled environment of a spreadsheet, the more I realized: prediction in the messy, complex real world is often a mirage.

“The map is not the territory — and a regression line is not the future.”

The Allure & Illusion of Prediction

We love predictions because they offer the illusion of control. A good forecast promises confidence in uncertain decisions. But as Roger L. Martin points out, all data comes from the past.

Statistical methods quietly assume that the future will behave just like the past — an assumption that works in stable systems but crumbles in complex ones.

This is where Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s work bites. In The Black Swan, he shows how rare, high-impact events dominate outcomes in many domains. These events are by definition unpredictable. Yet we persist in building models that pretend otherwise, leaving us overconfident and underprepared.

The real danger? Predictions fail silently. They look solid until the “surprise” arrives — and then fragility is exposed in full.

When Predictions Mislead

Rory Sutherland’s explore vs. exploit framing is relevant.

Exploitation — squeezing efficiency from what already works — favors prediction. Exploration — seeking new possibilities — is messy, probabilistic, and hard to model. Over-optimizing for exploitation often kills the seeds of future breakthroughs.

“The future isn’t a straight line; it’s a fat-tailed curve where a few events matter more than everything else.”

In fat-tailed systems, a handful of decisions or events create disproportionate impact. The pumpkin spice latte wasn’t a predictable hit on a marketing spreadsheet, yet it redefined Starbucks’ brand.

And sometimes, changing perception beats predicting performance. Adding the Overground to the London Tube map boosted ridership without laying a single new track. A simple paceometer changes driver behavior without a single engineering upgrade. These shifts don’t require forecasting — just reframing.

The Creativity vs. Data Paradox

Roger L. Martin draws a sharp line between strategy as a creative act and planning as data extrapolation. Aristotle saw it centuries ago: science works for “things that cannot be other than they are” — like gravity. For “things that can be other than they are” — like human behavior — we need rhetoric, imagination, and creativity.

Yet in modern business, we often demand predictive data to justify new ideas, but never for the status quo. This creates a self-sealing system: new ideas die for lack of “proof,” while existing ones roll on without challenge.

Martin’s challenge is simple but radical: when someone asks for data to defend an innovation, ask them to provide data that the current approach will keep working. That flips the burden of proof — and opens the door for creativity.

“If you can’t predict the future, design for it to surprise you in your favor.”

The AI Snake Oil Parallel

Arvind Narayanan’s AI Snake Oil offers a modern cautionary tale. Many AI systems claim near-magical predictive powers — in hiring, policing, sentencing — but often on shaky foundations. Just as my early Minitab regressions gave me false confidence in process outcomes, these AI models wrap the same fragile assumptions in more complex math.

The hype cycle makes this worse. The shinier the technology, the more its predictions are taken as fact — even when they’re just as exposed to rare events, shifting contexts, or behavioral changes.

Moving Beyond Prediction to Robustness

If prediction is unreliable in complex systems, what’s the alternative? Taleb’s antifragility is one answer: stop trying to guess the future and start building systems that can benefit from volatility and shocks.

From Sutherland, we learn the value of slack — deliberate inefficiency that allows exploration and serendipity. In a fat-tailed world, a single breakthrough from exploration can outweigh years of perfect exploitation.

From Martin, we learn that creativity is not a “nice to have” — it’s a competitive necessity. Leaders who can resolve trade-offs, spot anomalies, and imagine compelling futures without waiting for a spreadsheet are the ones who shape the curve, not just follow it.

“Stop asking ‘What will happen?’ — start asking ‘What will we do if it happens?’”

Closing Reflection

My early faith in Minitab’s regression models wasn’t wasted — it taught me rigor and the language of data. But it also taught me a bigger lesson: the map is never the territory.

The most valuable decisions I’ve seen were not the ones backed by the cleanest forecasts, but the ones made by people who knew when to ignore the model, when to explore, and when to reframe the problem entirely.

Prediction still has its place — but in a complex, fat-tailed, deeply human world, resilience, adaptability, and creative courage matter far more. The future is too important to be left to the past.