The Art of Spending Money by Morgan Housel

The Obituary Test

Here's an uncomfortable exercise: Write down what you want your obituary to say, then figure out how to live up to it.

Go ahead. I'll wait.

You probably wrote something about being loved, respected, helpful. About being a good parent or friend. Maybe about making a contribution to your community.

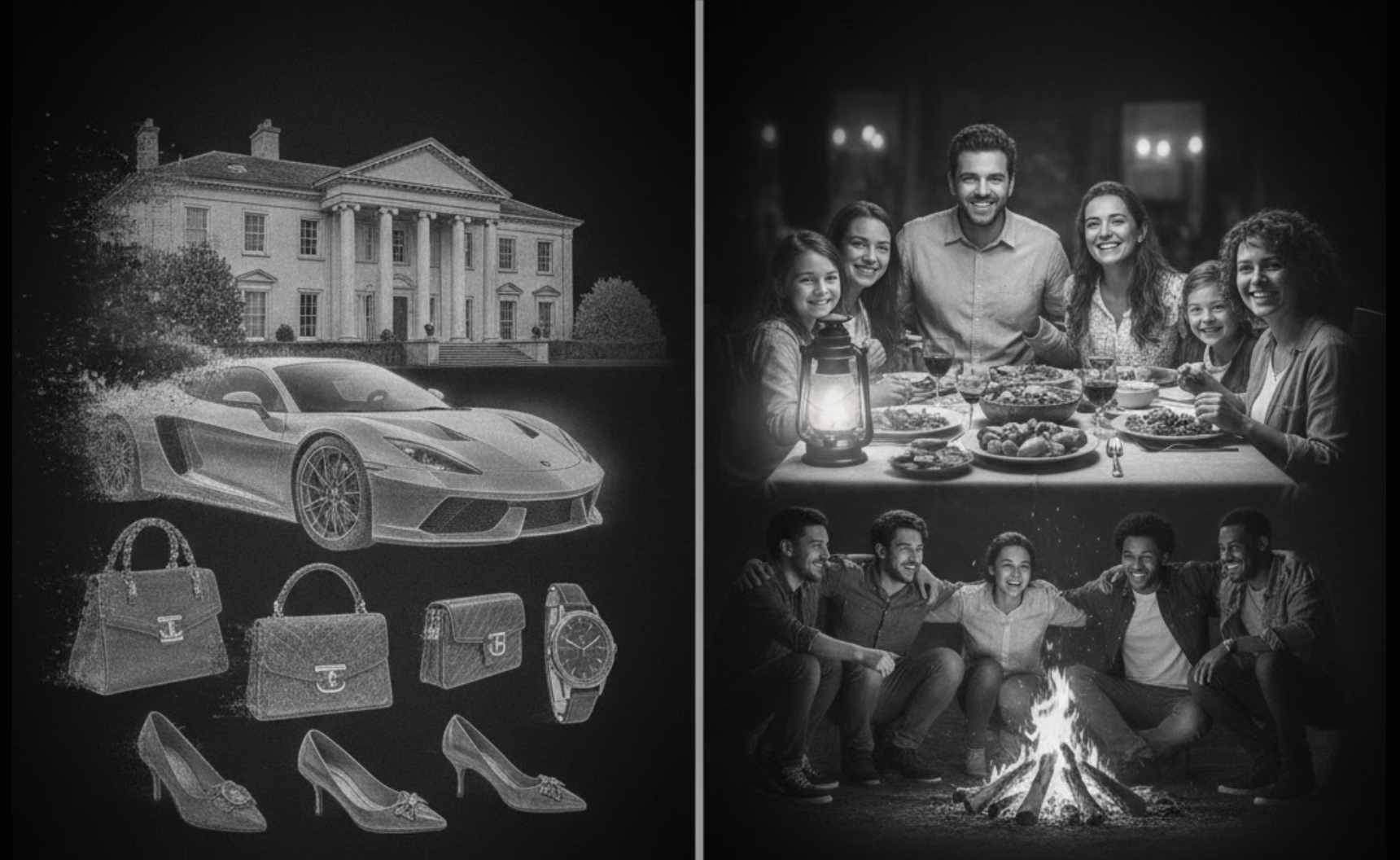

Notice what you didn't write? Nothing about your car's horsepower. Nothing about your home's square feet. Nothing about Italian marble countertops.

Yet look at your credit card statement. We're spending our lives chasing things we don't actually want mentioned at our funeral.

Morgan Housel's "The Art of Spending Money" exposes this gap between what we claim to value and how we actually spend. And it hurts to read—in the best way possible.

The Attention Economy of Your Wallet

Housel nails why we do this: "We value the attention money brings us more than we value the comfort and convenience of stuff that money can buy."

That's the trap. You buy the fancy car. Your neighbor notices. Feels good. But here's what happens next: "If I'm impressed with your car today, I might give you a little attention. But tomorrow the shock wears off a little. A month from now I yawn when I see your car. A year from now I couldn't care less."

So you upgrade again. And again. Always chasing that first hit of attention that wore off within weeks.

The book argues something radical: "Good advice is never as simple as saying 'Live for today' or 'Save for the future.' The only good advice is 'Minimize future regret.'"

Think about that job offer. One pays $60,000 for 45 hours a week. Another pays $50,000 for 35 hours. The math says take the first one—that extra $10,000 compounds to $1 million over 30 years. But the second option gives you back 500 hours per year. That's 15,000 hours of potential memories over your career. Those memories compound too. Which choice creates less regret?

The Fifteen Levels of Freedom

The book's most useful framework maps independence across fifteen levels. It's brutally honest about where most of us actually are versus where we think we are.

The 15 Levels of Financial Independence

- Level 0: Total financial dependence on the kindness of strangers who have no vested interest in your success. Complete lack of control over your financial life.

- Level 1: Complete financial dependence on people who want you to succeed because they like you and their reputation is attached to your success (parents, family, friends).

- Level 2: The ability to partially support yourself by adding value for others while still somewhat reliant on external support.

- Level 3: The ability to fully support yourself by adding value for others, but with a value that is marginal and easy to replace. You can pay all your bills, but a boss or customer still owns your day.

- Level 4: Enough savings to cover run-of-the-mill problems. A small medical bill, higher heating costs, new pants for your kid—you're OK.

- Level 5: Enough savings to cover larger, unforeseen problems. Your car breaks down, your furnace breaks—you're OK for a reasonable period of time.

- Level 6: Some retirement savings, education savings, and the avoidance of credit card debt. You can foresee a time when your current savings will grow into real independence.

- Level 7: The ability to pick a job that avoids the most egregious examples of bullshit and unnecessary hassles. You can say "No, not you. You're a terrible boss" and find someone else to work for. (If you make it here, you're crushing it.)

- Level 8: Becoming comfortable enough with your socioeconomic status that you don't feel the need to show off to strangers. The first glimpse of intellectual and identity independence.

- Level 9: The ability to avoid most debt, including auto loans, student loans, and even mortgages. Debt costs you future options and career independence.

- Level 10: Few realistic economic situations would push you back below Level 5. You could support yourself for a year or more off liquid savings. The first true stage of financial independence.

- Level 11: Passive income like interest and dividends covers a meaningful portion of your living expenses. You still work for a paycheck, but your portfolio is reducing common stresses.

- Level 12: Your investments and their reasonable return expectations will cover basic living expenses for longer than your life expectancy. You are no longer reliant on others for work.

- Level 13: Your assets and their reasonable return expectations cover above-basic living expenses. You can live the lifestyle you prefer and have something left over for family or charity.

- Level 14: Your independence lets you do and say what you please, unconcerned with other people disagreeing with you. "No thank you, I'm not interested" money.

- Level 15: You wake up every morning realizing you can spend your time doing what you want, with whom you want, for as long as you want. You beat the game. 99.99% of humans who have ever lived have not experienced this.

Most of us are stuck between 3 and 7, thinking we need to reach level 15 to be free. But Housel shows how each step up provides real freedom. Level 4 is just having enough to handle run-of-the-mill problems without getting wiped out. That's independence over life's daily hassles. And it changes everything.

The Contrast Principle

One of the book's most counterintuitive insights: "A simple life can be the most potent way to enjoy luxury items."

Housel explains through the power of contrast. Christmas morning feels magical because it happens once a year. That occasional nice dinner feels incredible when you usually cook at home. But when luxury becomes constant, it becomes invisible. "The power of contrast can make ordinary things feel incredible and extraordinary things feel bland."

He quotes Ramit Sethi's perfect formula: "You should spend extravagantly on the things you love as long as you mercilessly cut the things you don't."

Sethi loves clothes but isn't a car guy, so he dresses rich and drives cheap. He's figured out what actually brings him joy versus what he thought should bring him joy.

That's the real work—separating the two.

Coincidentally, Brain Sykes talks about "Intentional Discomfort" being good for the brain in his Youtube Short on travelling around the US for the next 3 years.

Also do look up: Hedonic Treadmill

What Your Kids Already Know

The chapter on kids and money is quietly devastating. You think you need to sit them down for explicit lessons about financial responsibility. You don't. They've been taking notes their whole lives.

Every time you said "we can't afford that" or "I love that we bought this"—they cataloged it. They noticed what made you happy when you got a raise and how scared you looked when you got laid off. "They see what you value. They watch what you waste."

One study showed 80-90% of kids adopt their parents' political views, even though most parents never give formal political lectures. The kids just pay attention. Money works the same way. Your spending is teaching them what matters, whether you mean to or not.

Head Meets Heart

Housel dismantles our obsession with measuring everything. Ask someone what memories with their kids are worth, and they'll say it's impossible to put a number on it. "But if I said, 'What is the fair market value of the home where you formed memories with your kids?' you could probably spit out a dollar figure with ease."

We can price the stage but not the performance. We can value the venue but not the experience.

His conclusion: "The best decisions probably happen at the intersection of the two—head and heart. The sweet spot with money is someone who is driven by equal parts rational math and emotional joy."

Sethi's Tactics Meet Housel's Philosophy

If you've read Ramit Sethi's "I Will Teach You To Be Rich," you know the tactical playbook: automate savings, crush debt, build systems that work while you sleep. Sethi teaches you how to make money work.

Housel teaches you why that matters and what to do once it's working.

Both authors hate the "$3 latte question" when $30,000 questions determine your future. Both champion guilt-free spending on what you love. But Sethi gives you the infrastructure. Housel gives you the philosophy.

Read Sethi first to build the foundation. Read Housel to understand what you're building it for.

The Formula

Housel keeps returning to one idea: "The simplest formula for a pretty nice life is independence plus purpose."

Independence to do what you want. Purpose to want to do meaningful things.

Not independence to impress strangers. Not purpose defined by Instagram. Just the quiet freedom to spend your time on things that will matter when you're writing that obituary.

The book won't tell you exactly how to spend your money. It'll do something harder—it'll make you question why you spend it the way you do.

And once you see the gap between your funeral and your credit card statement, you can't unsee it.